Immaginario Contemporaneo – Arte e Fotogiornalismo

Testo italiano in basso

The memory and rage of images

Newspaper and television images invade our lives like a visual storm, day after day, creating a parallel reality that intertwines with our individual and collective paths, running the risk of becoming confused with them. Perhaps this close encounter between living reality and the reality broadcast by the media can explain why mediated reality, clinging like a second skin to the immediate world, has become fertile territory for investigation on the part of artists. The “landscape” of the newspaper replaces that of the countryside, the “still life” of magazines replaces that prepared by the painter in his studio.

Media “deliver perceptible reality to the home”, said Paul Valéry, and they function as windows on the world, orienting our viewpoint and perception of the present, the past and probably the future. We are all aware – though in practice we tend to forget – that every photograph implies a perspective, that every publication inevitably takes a position. Interpretation is not limited to the choice (or omission) of verbal or visual content, but also extends to the form of representation: meaning is conveyed by the position of an article in a newspaper, its size, the layout, the size and cropping of the photograph, the caption.

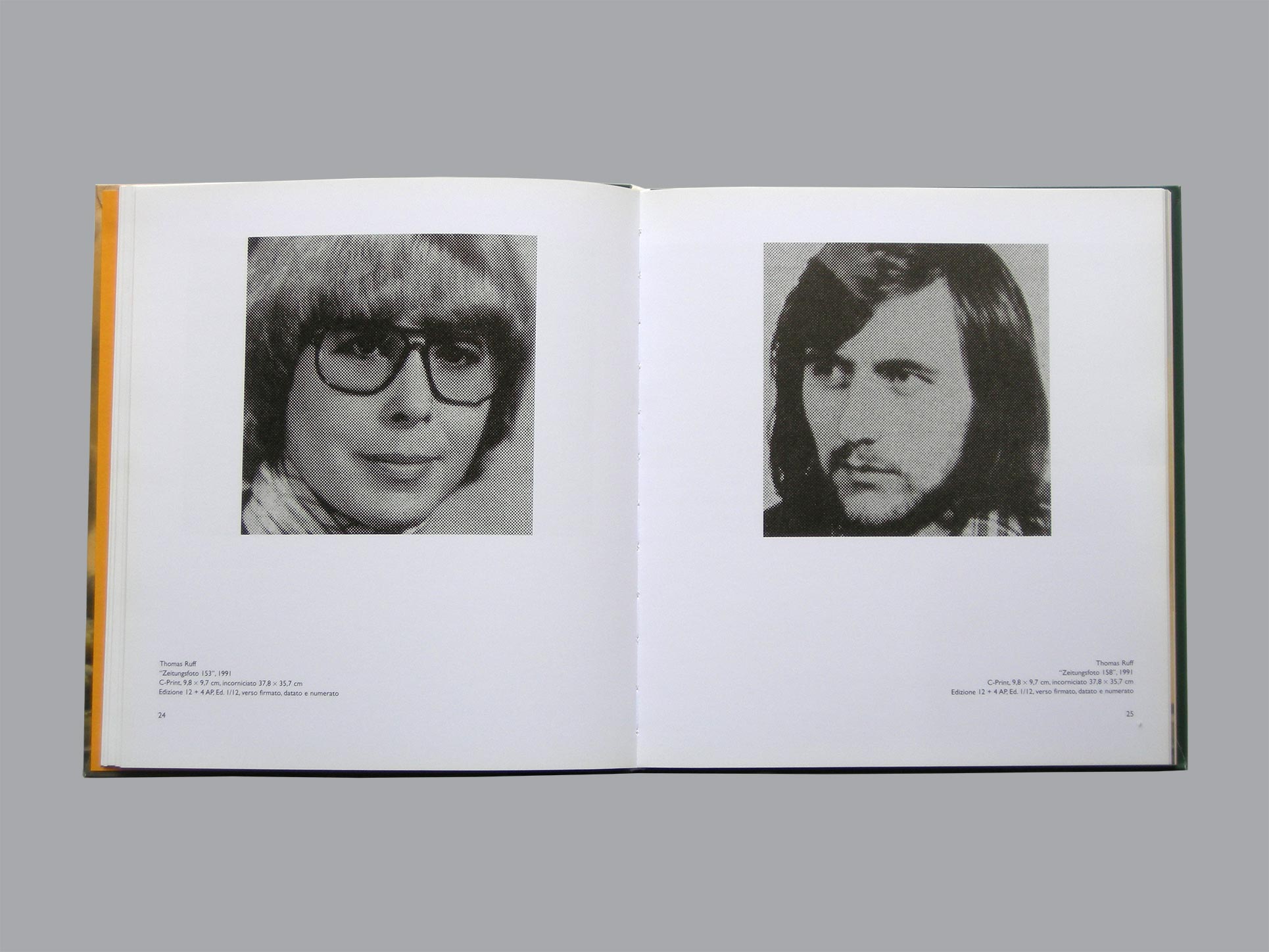

The empirical investigation Thomas Ruff began in the 1980s in the field of print media, collecting over 2500 images, provides concrete materials for an attempt to understand the use and function of photography in newspapers. The artist has focused on the quality of the images, in which journalistic criteria and information value prevail over artistic intent or formal research. In the edition Zeitungsfotos the 400 examples maintain their original screen and cropping, but they are enlarged 2:1 and the captions are removed. Separated from their content/media context, the pictures take on a dynamic of their own, narrating contemporary history as autonomous aesthetic impulses, facilitating access to their true iconographic message. “What information value remains in a newspaper photo”, the artist asks, “if we separate the image from its function?”

Ruff’s concerns, in their silent display, also address the perceptible presence of another particular quality of journalism: its speed and sort shelf life. “Journalists live on the ephemeral. They write and discard, discard and write”, says Gianni Riotta in an intriguing piece in which he compares journalistic output with Tibetan mandalas, continuously done and undone.

The ephemeral character of information is expressed with even greater force in the virtual quality and movement of television. These images, not borne on any surface or material, are made of pure light, and they dissolve as quickly as they appear. In his analysis of communication, Giovanni Bai goes beyond decontextualization: he literally breaks down images, in pieces, exploiting interference and amplification to alter their forms, or he manipulates refraction effects to obtain paintings composed of patterns and grids in which the colors are heightened, as in an expressionist painting or an acid trip. Bai accentuates the fluidity and fleeting nature of electronic media to show us where the continuous acceleration of our thirst for information may lead: to the breakdown of images, of language and meaning. To silence, in the end.

Unlike Bai, Thomas Ruff’s intervention saves photographs from an early demise, transforming them into witnesses of our time. In doing so, the artist gives visual form to a mechanism of our mind: some of the images, probably those of greatest impact, survive by depositing themselves in our memory, forming a sort of collection of archetypes. From passive reception these materials move toward an increasingly active role, becoming tools of interpretation and constitution of our reality itself.

The work of Gianluigi Colin highlights this slow depositing of fleeting images: unlike Ruff, Colin establishes a relationship between news photographs and the icons of art history, outlining surprising parallels of visuals and content. Goya’s Disasters of War, from the second decade in the 1800s, show the same scenes as certain photographs from Iraq today: we ask ourselves if it is the tragic content that gives rise to repetition in each new occasion, or if instead there are cultural archetypes rooted in our consciousness, or in the subconscious mind of the person who took the pictures. Can we hypothesize a contemporary imagery composed of visual impressions drawn from both the history of art and the flow of photojournalism, which forms the basis for our orientation when we look for images? Do we find what we are looking for because the picture to be taken is already there in our memory?

Representations speak different languages: meanings are not restricted to aspects of narration, form and composition, but also reflect underlying power structures. Ian Anüll extends his iconographic investigation to the social values contained in images, signs and brands (® Registered Trademark), attempting to analyze their shifts of meaning. His installation “Tokyo Bourse” documents the tragic side of disrupted values. In the enlarged photograph some Japanese brokers, in despair over the stock market crash, furiously throw devalued paper into the air. Stripped of its speculative function, the documents lose their meaning and become mere pieces of paper, which the artist has symbolically scattered on the floor of the gallery.

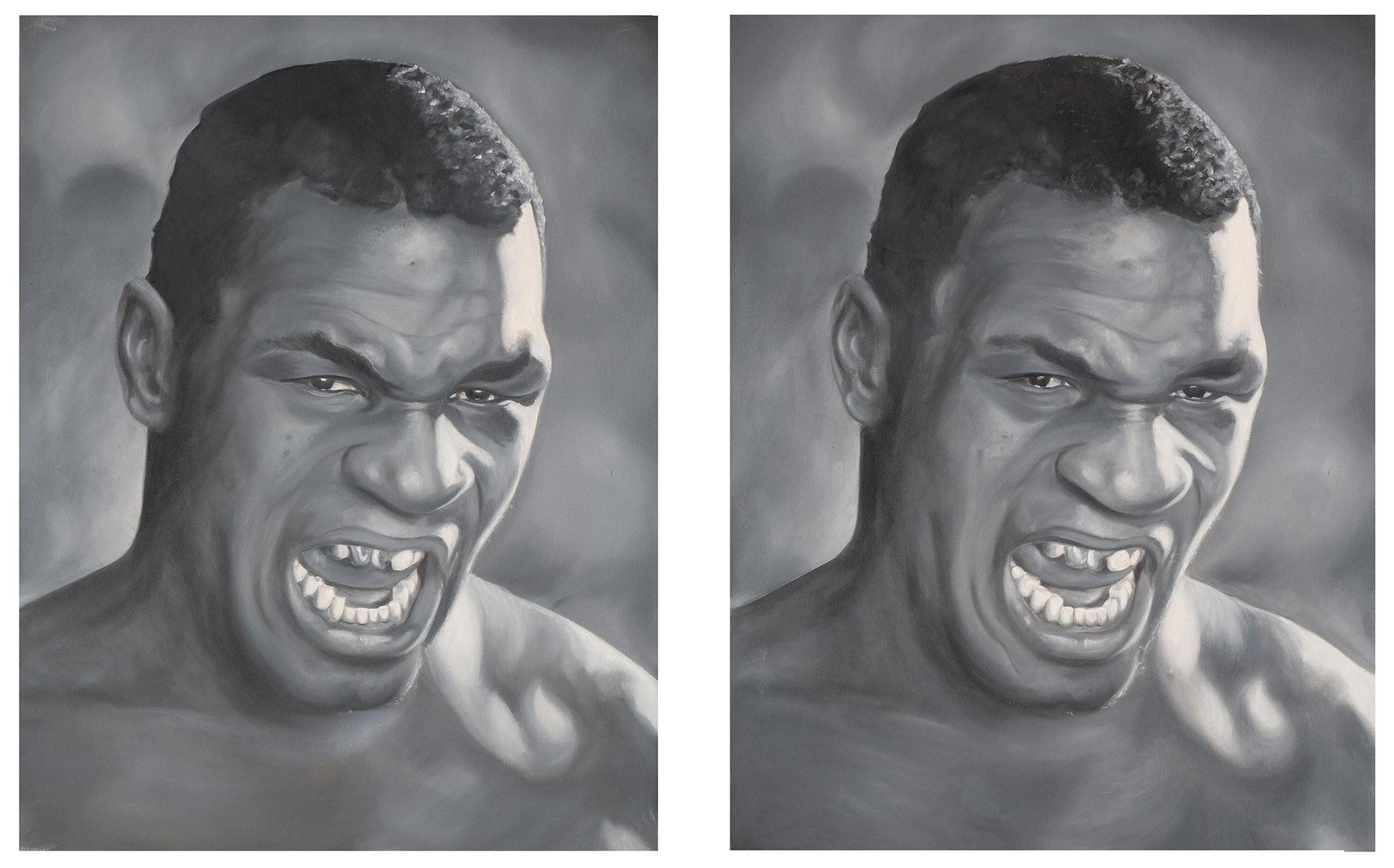

Even reproductions have lost their value. Not in financial terms, as for stocks, but in terms of authenticity, the unique quality of the artwork. According to Walter Benjamin their aura (“unique apparitions of a distance, to the extent that it can be approached”) has been replaced by fleeting, repeatable observation. A series of events has taken the place of a unique event. In a game of redistribution of values, Gabriele Di Matteo regenerates the uniqueness and durability of newspaper photos, by reproducing them in large paintings. The “copy” painted by the artist’s hand (or that of his alter ego) achieves the status of an “original”. But the artist’s cunning doesn’t stop here: he produces several specimens of each painting, clones that may look the same but end up never being precisely identical, because they are made by hand. The works of Gabriele Di Matteo are reproductions (of the newspaper) but also originals (because they are painted). Thus they are repeatable but unique: simultaneously volatile and durable. This contradiction sheds light on the question of the legitimacy and possibility of painting in the era of mass media: it would appear that some doors have remained open, through which we can hear echoes of the memorable days of portraiture and landscape painting.

The reproduction of the pictures from the newspaper, subtracted and reworked by the artists, takes on the status of an original artwork. The passage from mass distribution to uniqueness involves the same mechanism found in the readymades of Duchamp, in which “manufactured objects [are] promoted to the dignity of objects of art through the choice of the artist”, as André Breton wrote in the Dictionary of Surrealism (1938). The passage from one category to the other takes on different forms: while Ruff and Anüll reproduce the photograph, enlarging it and removing it from its context, Bai breaks up the raw material, Colin proceeds by analogies, Di Matteo repaints and Viel re-draws the subject from the printed paper.

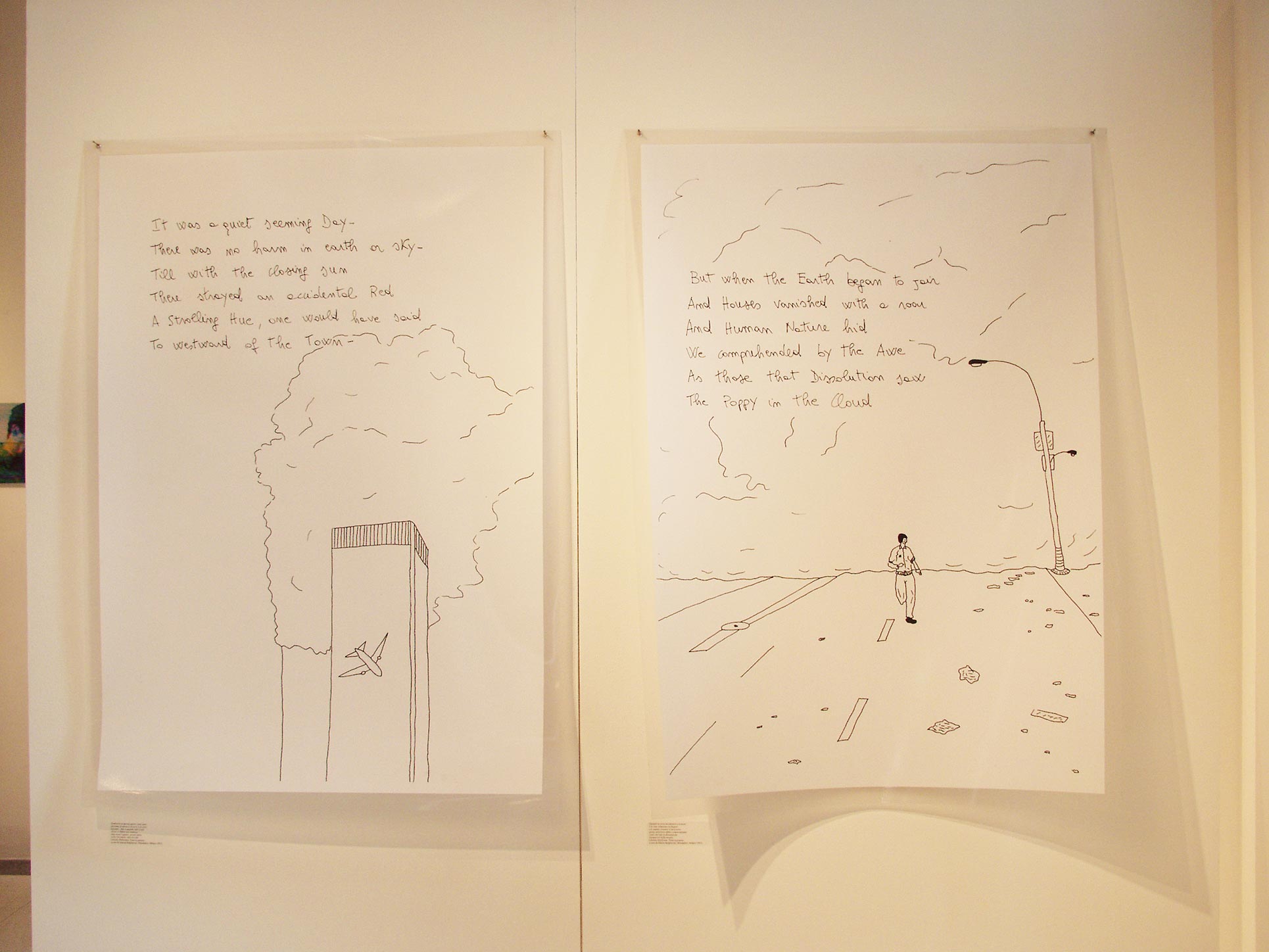

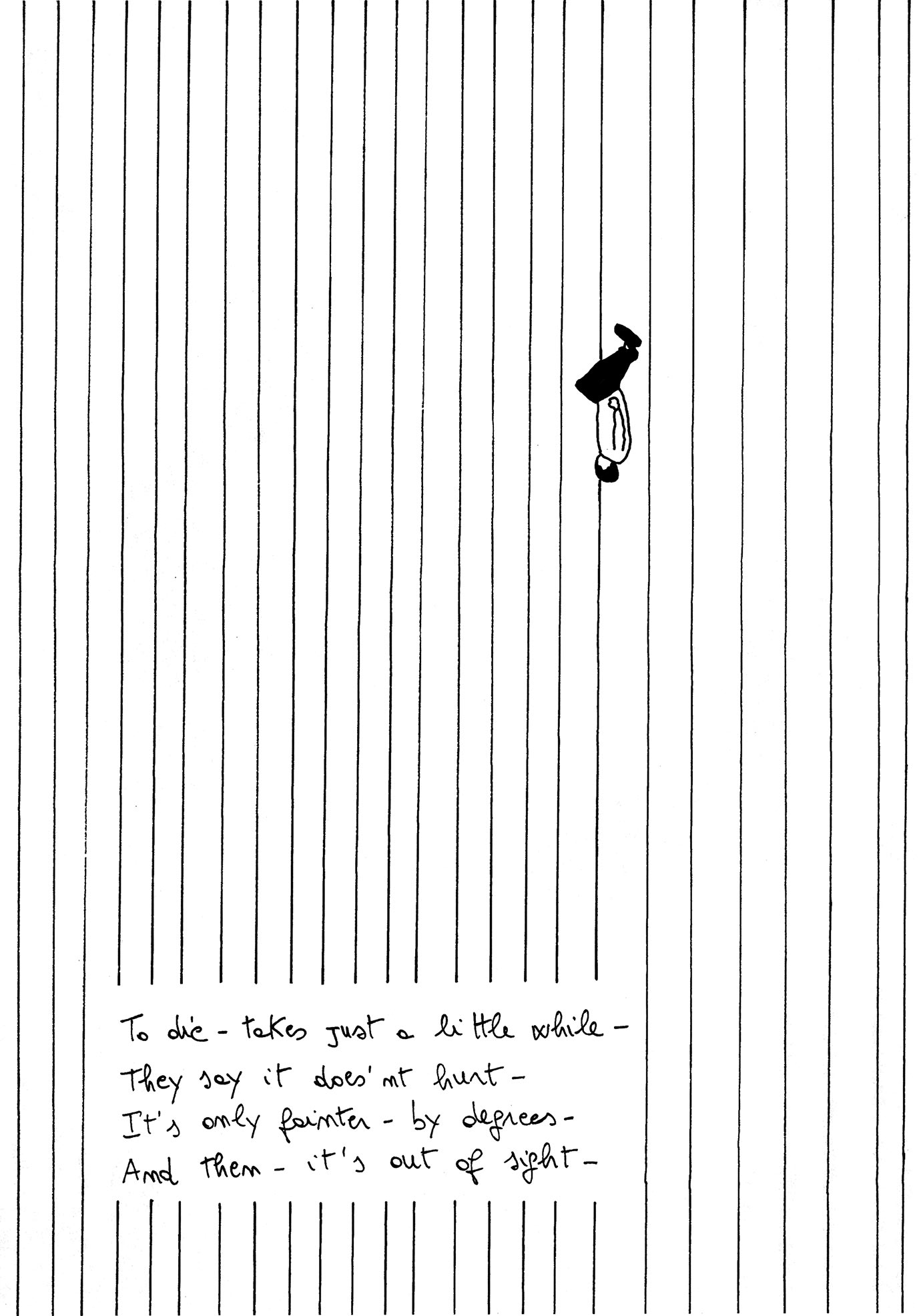

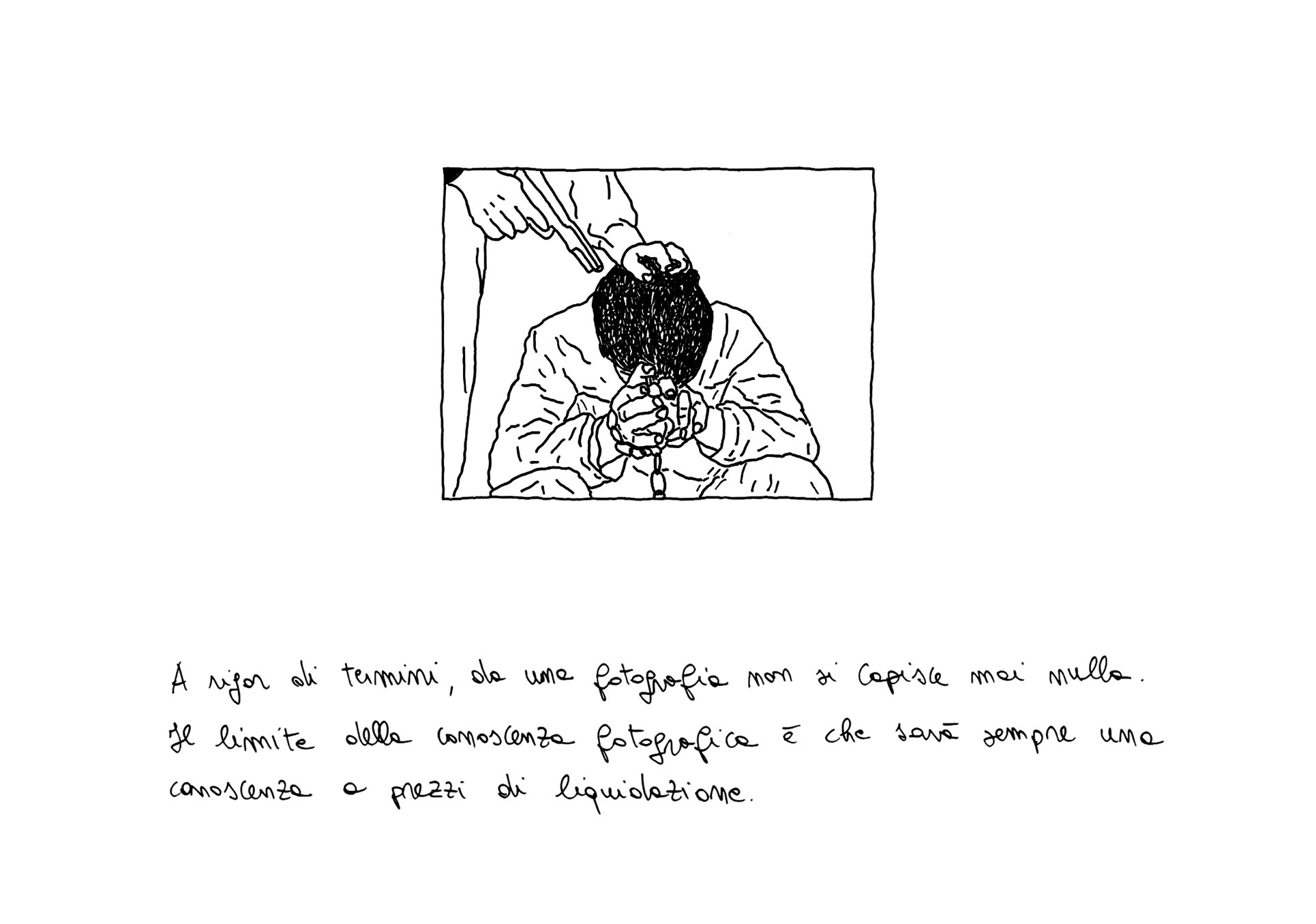

In his Contemporary Diary Cesare Viel takes the word “appropriation” literally: it becomes a sort of absorption of the object in the subject. The first step of his subjectivizing of (apparently) objective materials consists in tracing, with slender lines, the contours of a newspaper photo. This technique, a gesture that already alludes to writing, is combined with quotations from various authors handwritten by the artist. The words of writers like Susan Sontag, Virginia Woolf or Emily Dickinson add an emotional and subjective impact, urging deeper interpretation. Image and word seek one another, and the approach between visual and verbal representation creates new meanings, opening up other poetic spaces. Among the various possible relationships, Viel rarely makes do with a mere indicative caption, but attempts to flank the drawings with visionary phrases from the past, to elevate the transient image into the realm of universal human concerns.

The rage of images, their flow, their apparition and vanishing, their accumulation to create textures of meaning reflect our world, constitute it and dismember it in a continuous game of reminders. The instant obsolescence of media imagery seems to be trying to reflect the fragility of our life, while their everyday resurfacing reminds us of the capacity of life itself: its possibility of continuous recomposition.

Barbara Fässler

La memoria e la furia delle immagini

Le immagini di giornali e televisioni invadono come una tempesta visiva, giorno dopo giorno, la nostra vita e creano una realtà parallela che si intreccia con i nostri percorsi individuali e collettivi, anzi rischia di confondersi con essi. Forse questo avvicinamento tra realtà vissuta e realtà trasmessa dai media è il motivo per cui la realtà mediata, aderente come una seconda pelle a quella immediata, sia diventata un terreno fertile per le indagini degli artisti. Il “paesaggio” del giornale sostituisce il paesaggio di campagna, la “natura morta” del periodico quella preparata nello studio dell’artista.

I media “distribuiscono la realtà sensibile a domicilio”, diceva Paul Valéry, e funzionano come finestre sul mondo che indirizzano il nostro punto di vista e la nostra percezione dell’oggi, dello ieri e probabilmente anche del domani. Lo sappiamo tutti - ma nella prassi tendiamo a dimenticarcene - che ogni scatto fotografico implica una prospettiva e che ogni pubblicazione include una presa di posizione. L’interpretazione non si limita alla scelta (o all’omissione) del contenuto redazionale verbale e visivo, ma si estende alla forma della rappresentazione: contribuiscono al senso la posizione del servizio all’interno del giornale, la dimensione dell’articolo, gli elementi dell’impaginato, la dimensione e il taglio della fotografia e infine l’abbinamento alla didascalia.

L’indagine empirica che Thomas Ruff ha avviato negli anni ’80 nel campo della carta stampata, collezionando oltre 2.500 immagini, fornisce materiali concreti per cercare di comprendere l’utilizzo e la funzione della fotografia nei giornali. L’interesse dell’artista si è focalizzato sulla qualità di tali immagini, nelle quali i criteri giornalistici e i valori d’informazione prevalgono sull’intento artistico e sulla ricerca formale. Nell’edizione “Zeitungsfotos” i 400 esempi mantengono il retino e il taglio originali, ma sono ingranditi in scala 2:1 e privati dalla didascalia esplicativa. Separando le fotografie dal loro contesto mediatico e contenutistico, essi sviluppano una dinamica propria, narrano la storia contemporanea in quanto spunti estetici autonomi e liberano l’accesso al loro vero messaggio iconografico. “Quale valore informativo rimane in una fotografia del giornale”, si chiede l’artista, “se separiamo l’immagine dalla sua funzione?”

Le preoccupazioni di Ruff ci parlano nella loro silenziosa esposizione dei fatti sensibili di un’altra peculiarità del giornalismo: la sua velocità e caducità. “Il giornalista campa di effimero. Scrive e butta, butta e scrive”, dice Gianni Riotta in un bellissimo testo, nel quale paragona il prodotto redazionale al mandala tibetano che si crea e si disfa in continuazione.

Il carattere effimero dell’informazione si esprime con maggiore forza nella virtualità e nel movimento della televisione. Questi fotogrammi, privi di supporto e di materialità, sono fatti di pura luce e si disciolgono nello stesso momento in cui appaiono. Nella sua analisi della comunicazione, Giovanni Bai va oltre la decontestualizzazione: egli scompone letteralmente le immagini, le fa a pezzi, sfruttando le interferenze e le amplificazioni per alterare le forme, oppure manipola gli effetti di rifrazione per ottenere dei quadri composti da trame e griglie in cui i colori si esaltano come in un quadro espressionista o in un trip psichedelico. Bai esaspera la fluidità e la fuggevolezza dei media elettronici, per dimostrarci dove ci può portare la continua accelerazione della nostra sete d’informazione: alla dissoluzione delle immagini, del linguaggio e del senso e, infine, al silenzio.

Al contrario di Bai, l’intervento di Thomas Ruff salva le fotografie dalla loro morte precoce e le trasforma in testimoni del nostro tempo. Con ciò l’artista visualizza un meccanismo nella nostra mente: alcune delle immagini, probabilmente quelle di più forte impatto, sopravvivono sedimentandosi nella nostra memoria, formando una sorta di collezione di immagini archetipiche. Dalla ricezione passiva questi materiali guadagnano un ruolo sempre più attivo e diventano strumenti di lettura e di costituzione della nostra stessa realtà.

L’opera di Gianluigi Colin evidenzia questa lenta deposizione delle immagini sfuggenti: a differenza di Ruff, Colin mette le fotografie dell’attualità giornalistica in relazione con le icone dalla storia dell’arte, delineando un sorprendente parallelismo di visuali e di contenuti. I “Disastri della guerra” di Goya, del secondo decennio dell’800, ritraggono le stesse scene di alcune fotografie dell’Iraq dei nostri giorni: noi ci chiediamo se sia il contenuto tragico a dare luogo alla ripetizione in ogni nuova occasione, o se esistono invece archetipi culturali ancorati nella nostra coscienza o nell’inconscio di chi scatta le foto di cronaca. Si può ipotizzare un immaginario contemporaneo costituito da impressioni visive, provenienti sia dalle icone della storia dell’arte che dal flusso della fotocronaca, che ci guida nella nostra ricerca di immagini? E ancora, troviamo ciò che cerchiamo perché l’immagine da scattare si trova già impressa nella nostra memoria?

Le rappresentazioni parlano linguaggi differenti: i significati non si limitano ad aspetti narrativi o formali e compositivi, ma riflettono le strutture del potere sottostanti. Ian Anüll estende la sua indagine iconografica ai valori sociali contenuti nelle immagini, nei segni e nei marchi (® Registered Trademark) e cerca di analizzare i loro mutamenti di senso. La sua installazione “Borsa di Tokyo” documenta il versante tragico dei valori stravolti. Nella fotografia ingrandita dal giornale alcuni broker giapponesi, disperati dal crollo della borsa, buttano infuriati in aria le azioni ormai prive di valore. Spogliate della loro funzione speculativa, le azioni hanno perso il loro senso e sono diventate dei semplici fogli di carta che l’artista ha simbolicamente sparso sul pavimento della galleria.

Anche le riproduzioni hanno perso il loro valore. Non quello finanziario come accade per le azioni, bensì quello dell’autenticità e dell’unicità proprie dell’opera d’arte. Secondo Walter Benjamin, la loro aura (“apparizioni uniche di una lontananza per quanto questa possa essere vicina”) è stata sostituita da un’osservazione fugace e ripetibile. Una serie di eventi ha preso il posto di un evento unico. In un gioco di redistribuzione dei valori, Gabriele Di Matteo ripristina l’unicità e la durata delle fotografie del giornale, dipingendole in quadri giganti. La “copia” dipinta dalla mano dell’artista (o del suo alter ego), si eleva allo stato di originale. Ma l’astuzia dell’artista non si ferma qui: egli produce i suoi dipinti in vari esemplari, cloni che possono sembrare uguali, ma che finiscono per non essere mai esattamente identici perché sono fatti a mano. Le opere di Gabriele Di Matteo sono riproduzioni (dal giornale) originali (perché dipinti) e quindi ripetibili ma uniche: labili e durevoli al contempo. Da tale controsenso emerge la questione della legittimità e possibilità della pittura nell’era dei mass media: a quanto pare qualche porta è rimasta aperta, e da essa risuona un’eco proveniente dai memorabili tempi della pittura ritrattistica e paesaggistica.

La riproduzione dalla testata giornalistica, sottratta e rielaborata dagli artisti, si innalza ad opera d’arte originale. Il passaggio dalla diffusione di massa all’unicità segna lo stesso meccanismo del ready made di Duchamp, in cui «un oggetto usuale è promosso alla dignità di opera d’arte tramite la semplice scelta dell’artista”, come lo definisce André Breton nel Dizionario del Surrealismo (1938). Il trapasso da una categoria all’altra assume forme diverse: mentre Ruff e Anüll riproducono la fotografia ingrandendola e decontestualizzandola, Bai scompone la materia prima, Colin procede per analogie, Di Matteo ridipinge e Viel ridisegna il soggetto dalla carta stampata.

Nel suo “Diario contemporaneo”, Cesare Viel prende la parola “appropriazione” alla lettera: essa diventa una sorta di fagocitazione dell’oggetto nel soggetto. Il primo passo della sua soggettivizzazione dei materiali (apparentemente) oggettivi consiste nel ridisegnare a tratto sottile i contorni della fotografia dal giornale. A questa tecnica, che nel suo gesto allude già alla scrittura, si abbinano citazioni di vari autori, manoscritte dall’artista. Le parole di scrittori quali Susan Sonntag, Virginia Woolf o Emily Dickinson aggiungono un impatto emotivo e soggettivo e indirizzano la lettura in profondità. Immagine e parola si cercano e l’avvicinamento tra rappresentazione visiva e verbale crea significati nuovi e apre ulteriori spazi poetici. Tra i vari rapporti possibili, Viel si ferma raramente all’uso della didascalia denotativa, ma cerca di avvicinare ai disegni frasi di portata visionaria per elevare con ciò l’immagine fuggitiva a preoccupazioni umane universali.

La furia delle immagini, il loro fluire, il loro apparire e sparire, il loro depositarsi per creare tessiture di significati riflette il nostro mondo, lo costituisce e lo smembra in un continuo gioco di rimandi. La caducità delle immagini sui media pare voler rispecchiare la fragilità della nostra vita, senonché il loro quotidiano riaffiorare ci ricorda la capacità della vita stessa: la sua possibilità di continua ricomposizione.

Barbara Fässler

Curated by Barbara Fässler

Artists: Ian Anüll, Giovanni Bai, Gianluigi Colin, Gabriele Di Matteo, Thomas Ruff, Cesare Viel