Circus Maxximus

After 12 years of planning and construction, after seven changes of government, in the midst of the harshest economic crisis of the postwar period, the inauguration of MAXXI, the National Museum of 21st Century Art in Rome, costing a princely sum of 150 million euro, appears as some sort of miracle. To make it all the more incredible is the constant presence of the fairer sex in the establishment and in the future running of this institution.

In fact the building, located in the suburb of Flaminio, was designed by the British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid, and the museum will be directed by Margherita Gruccione (MAXXI Architecture) together with Anna Mattirolo (MAXXI Art). Notwithstanding the risk of politics wanting to appropriate a project of such scale, and that someone could exploit it to raise their own personal prestige, the event is to be valued very positively at a time of serious economic and cultural stagnation. In other words, I don’t believe that the media circus, the starlets and the VIP’s of the world of politics who attended the opening will be able to detract from the importance of the project, both from the architectural as well as artistic point of view, and even less so as regards its significance for the future of cultural politics in this country. The first days of its opening, when the rate of visitors reached 800 per hour, demonstrated that MAXXI could become an object of wide interest and gives hope that contemporary art and architecture will succeed in breaking free of its marginal status. This matter is of particular importance in a country such as Italy, where the protection and conservation of a vast heritage of art from times past has absorbed the greater portion of public finance earmarked for the arts. The new structure is managed by a foundation that was established by the Ministry of Culture, and holds a collection of more than 300 works by Italian and international artists: a mixture of installations, pictorial works, video art and photography, intended to be supplemented in the future.

Nevertheless, that which really is of interest more so than gossip are the issues regarding the contents and its relationship with the holder, the fragile balance between the architecture and the works of art that it hosts, rather than curatorial challenges in tension between what is promised and what is delivered.

Zaha’s museum breaks with the Euclidian space and presents us with an architecture that can wreak havoc with our perceptions and mix up our sense of orientation. The pavements on a slope make us go up and down, and the spaces, being characterised by numerous entrances, go off in all directions. To understand how this spatial system works, in which the viewers become actors in the flow, it is necessary to go around it more than once, in various directions, which each time make us discover yet another passage and, above all, a new vantage point.

Even after its showy opening, MAXXI will have to search for and gradually modify its own identity, and through concrete living to find its measure with a radically exceptional space. The rhizomatic and dynamic logic of this venue could be understood as a metaphor for an auspicious omen as regards the contents that it will contain. As its name promises, Museum of the 21st Century, ideally MAXXI should be turned to the future and we will see how the staff of directors and curators succeed in balancing the demands of conservation and archiving, directed towards the past, on the one hand, and a wish to represent that which is nascent on the other. The building which follows and embodies the ancient principle of “everything flows” calls for contents in harmony with its shapes: in this way MAXXI harks to flowing thoughts, dynamic events and unsettling works. And it will be precisely this that will be the most fragile and difficult task to carry out: to show the more experimental works by unknown artists always means running curatorial risks with values not yet critically “accepted”, and for curators to take the responsibility of upholding their own critical judgment, which at times may be uncomfortable and against the current.

In her article in the catalogue, Anna Mattiroli, the director of MAXXI Art, explains how the collection has grown in parallel with the construction works of the museum. This fact demonstrates that here architecture and art will continue to measure themselves against each other through a lengthy growing process, and that the museum is not limiting itself only to a representation of the two genres, but is seeking to bring them to life internally. The museum is inclined to a future of ‘work in progress’ and is taking part in this process as a perpetual workshop of experimentation. This kind of workshop in continual evolution investigates whether and how the work can react to the dimensional and formal demands of the building: a form that is flexible and open, but at the same time providing a stable base.

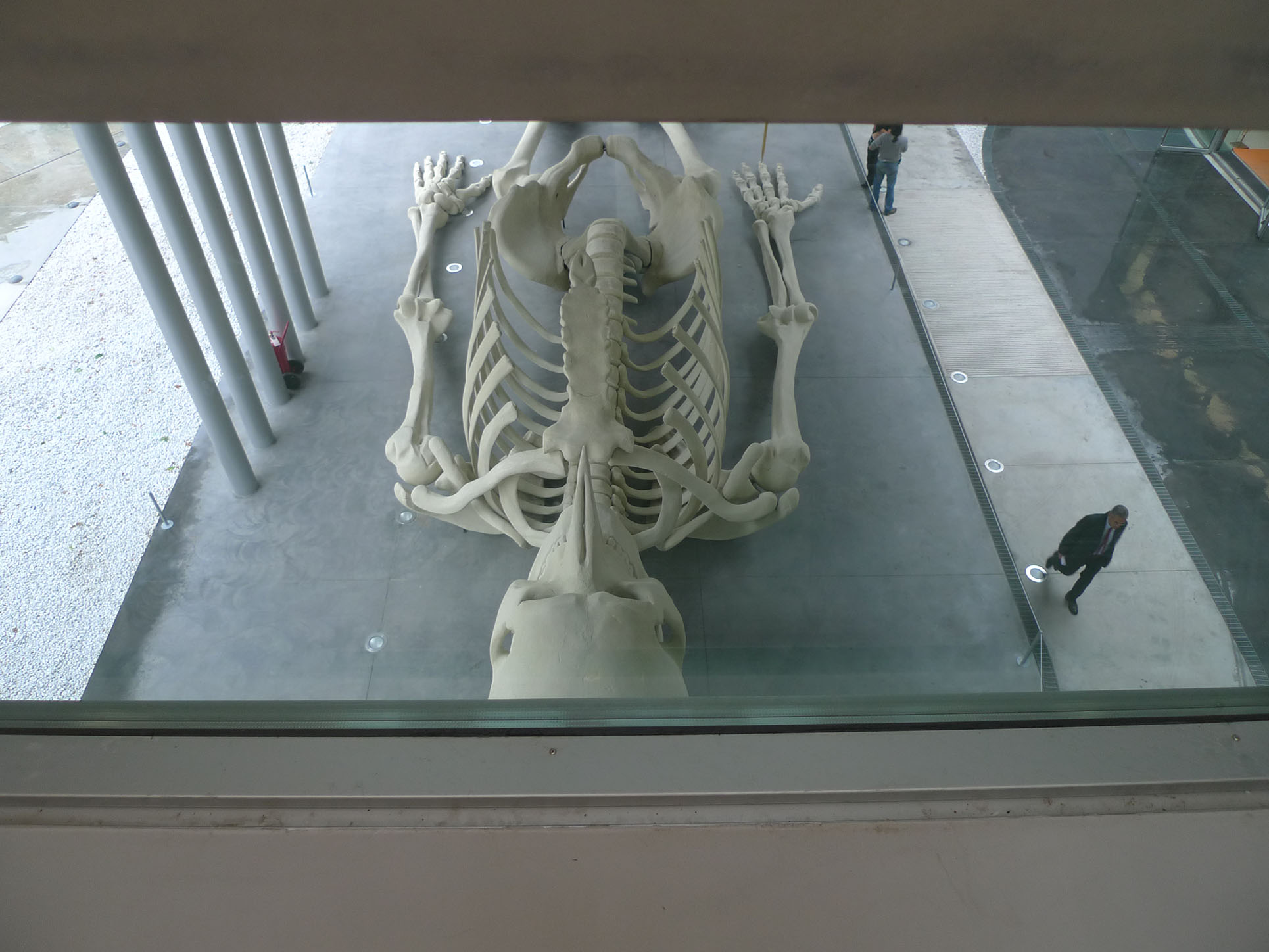

This dangerous balance is already clearly in evidence in the inaugural exhibitions, which seek to reconcile the real with the invisible, the highly sought-after with the unsaleable, traditional works with the experimental. The coup de theatre succeeds in grand style with the first ever retrospective – including a scientific monograph – of Gino De Dominicis, conceptual artist, until now unknown to the general public despite having participated in five Venice Biennials, one Kassel documenta and two Rome Quadrennials. The exhibition L’immortale (‘The Immortal’) of the artist from the region of Marche, class of 1947, of whom we lost trace in 1998, was curated by Achille Bonito Oliva. Even before entering the building, the exhibition opens with the grandiose Calamita cosmica (‘Cosmic Magnet’ 1989), a skeleton 24 metres tall with a 7 metre gold pole in its hand pointing into extra-terrestrial space. The gigantic body features a peculiarity which can then be observed in many of the paintings shown in the third part of the exhibition. His nose is extremely elongated and is evocative of our poor Pinocchio. One spontaneously wants to ask whether the artist (or art as such) is leading us by the nose [making fools of us], playing at being the king’s jester, or else it leads us to ponder upon the paradox of the liar who, in saying “I am lying”, lies if telling the truth, and tells the truth if lying.

De Dominicis does not reveal his secrets, on the contrary, as soon as we have entered the enormous Hall where the passerelles of Zaha ìHadid divide up the space in all directions, we are overcome by the sound of cosmic laughter of D’io, (‘God/of I’) , with which Gino once more makes fun of us. The first section presents purely conceptual works of the 1960s and 70s: some of them real gems. We find, for example, an empty ‘clock’ from 1970 which is silent, because it cannot fulfil its duty, that is: to measure time. Immortality is achieved here by the removal of the inevitable passage of time, and as a consequence – the finiteness of our days. The video work Tentativo di volo (‘Attempt to fly’, 2’, 1969) for its part ironises on another ancient unfulfilled desire of mankind: that of flying. We see the artist who climbs on a rock in order to jump down again, beating his arms in vain. We humans are unavoidably glued to the earth and it is not possible to overcome our corporeal existence. The black curvilinear passerelles in the central space lead us by various loops towards the top, up to Gallery 5 where the paintings from the last years of GDD’s life are hung. We pass from red men birds to blue ones, from small formats to medium sized works, in an idealized ascent from darkness to light. At the end of our climb we get to the last hall, where the gigantic pure gold paintings are displayed, and which reflect the dazzling light of the ‘eye’ of the museum, the glass front which looks out over the city, yet seems to allude another dimension. It is truly incredible how in this part of the museum the architecture interplays with the works in a sort of dancing crescendo towards ecstasy. For the first time, I really understood through the sensation of my body and not with the intellect, what the Neo-platonists meant by the ascent towards The One and the light. The idea of immortality is not limited to the subject of Gino De Dominicis, but extends through the figure of the artist and art in themselves as both being capable of leading us towards the light, towards the Universe, towards the immaterial, the spirit, and hence to resolution and liberation.

The second exhibition also – a selection from the MAXXI collection – underlines the primary importance of spatial interrelations and explores in a finely articulated development the theme on various levels. The show Spazio (‘Space’) was curated collectively by Pippo Ciorra, Alessandro D’Onofrio, Bartolomeo Pietromarchi and Gabi Scardi, and in a labyrinthine journey presents 75 works. By space the curators have meant both physical space as well as institutional space, but above all the context of the social, geographical, historic and cultural space in which we live and perceive, without omitting architectonic and urban space, and on top of that everything that is imaginary, of the theatre and virtual: all the fundamental notions that art gathers together within itself. The exhibition is divided into four sections: Naturale Artificiale (‘Natural Artificial’), Dal corpo alla città (‘From the Body to the City’), Mappe del reale (‘Maps of Reality’) and La scena e l’immaginario (‘The Stage and the Imaginary’).

‘Natural Artificial’ poses questions about how the architectonic space of the museum imitates the space of nature, its inconsistencies, its surprises, but also its visual harmony. An inhabited space which becomes a landscape, and which divides itself into varied paths and currents. The artists in this section highlight the relationship between the natural and the artificial, with completely different viewpoints and disparate materials. Mario Airò, for example, simulates dawn with a red light which emanates from behind a wooden profile of a mountain scene. On the other hand, La corda di carta di giornali (‘The Rope of Newspaper’), born of the long and patient labours of Stefano Arienti, brings a cultural object par excellence (a newspaper) back to a “natural” and organic form: a kind ofm snake which always adapts itself to the space in which it finds itself. In this section we can see, among others, important works by Joseph Beuys, Luciano Fabro, Gilbert & George, Anselm Kiefer, Thomas Ruff, Andy Warhol, as well as by younger Italians such as Claudia Losi.

In the ‘From the Body to the City’ section we find reflections on the relationship between personal space and public space, through understanding of one’s self and the surrounding space: the body which becomes the collective experience of the city as an ordered system, but also as a location of conflict and contradiction. Marina Ballo Charmet, for instance, observes the ‘background noise’ of our thoughts by means of the sections, corners and edges of urban space which we notice only through The Corner of the Eye, this ‘always seen’ to which we however do not pay the least conscious attention. Also the Stadtbild by Gerhard Richter offers us an abstract vision of reality: this time an aerial view of a bombarded Dresden, painted in black and white with powerful and decisive brushstrokes. Cesare Pietroiusti, on the other hand, provides a pointed and apt reflection on the marginalized status of the artist and vaguely raises again a theme visited by de Dominicis: the role of the artist in society. During the opening of MAXXI Pietroiusti locked himself in the service stairwell and described – this being transmitted in the hall with loudspeakers – for many hours all that he saw and how he was feeling. This section contains works by Maurizio Cattelan, Anish Kapoor, and also the more recent output by Alterazioni Video, Micol Assael etc.

On the other hand ‘Maps of Reality’ is preoccupied with the geopolitical aspects of drawing maps, and hence the projections of reality. Atelier Van Lieshout, for example, exhibits an urban plan of its Slave City, an utopian city which is self-sufficient and ecologically sustainable, where every minute of its inhabitants is regulated in order to avoid any kind of wastage, obviously to the detriment of personal liberty. Flavio Favelli, however, presents us with his Carta d’Italia Unita (‘Map of a United Italy’) which is made up of the pages from a road atlas, thus completing the entire ‘boot’ [of Italy]. Other names in this section are Giovanni Anselmo, Luca Vitone, Lawrence Weiner, Lucy e Jorge Orta.

‘The Stage and the Imaginary’ is the title of the last section of the exhibition: this for certain is the one most linked to the visionary aspect, and in consequence is less related to the physical side of space. The museum here takes the role of a production, and as a machine that communicates between fiction and reality. William Kentridge, for example, is spellbinding with his play theatre, presenting a very personal version of ‘The Magic Flute’: Preparing the Flute. Conversely Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, in Where is our place?, envelop us in a room composed of three spatial and temporal levels. The past is a magnified museum, the present is a story of photographs and love poems, and the future is a miniature model buried beneath our feet, and ready to emerge at any moment. In this section one can view, amongst other, the works of Giulio Paolini, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Sol LeWitt, Luigi Ontani, Bill Viola, Grazia Toderi and vedovamazzei.

We are limited here to speaking about the chief exhibitions of contemporary art with which MAXXI opened its doors, but this is not to deflect importance from another facet: MAXXI Architecture, which was inaugurated with an eloquent and detailed exhibition about Luigi Moretti, Dal razionalismo all’informale (‘From Rationalism to the Informal’), which showed the historic development, models and photographs of his work. In addition MAXXI offers a photographic archive, a Department of Education, a conference hall and a bookshop.

The rhizomatic and dynamic structure of the new museum will accompany us, in this still quite new century, towards new adventures which will combine architectural space and artistic research in a mutual interlinking of contemplation and confrontation. We hope that the means which they have at their disposal, for a satisfactory continuation of this undertaking, will remain at the same high level of the initial project, and that Italy and Europe will for a long time make use of this research laboratory which is capable of taking us, in the footsteps of thought and poetry, into the 22nd century.

Barbara Fässler