Ready-Made Planet

“A painting has value only if it is an entirety: it has no need to add, just to be.” (1)

For the artist Piero Manzoni (1933–1963), art is elementary ontological research, a scientific search for the fundament. He considers a painting as a space of liberty looking for the original image that surmounts any space of representation. A painting, which is analysed in its existence as an object, opens the way to endless material experiments as concretisation of thought. In Manzoni’s constant feverish research – which required only eight years – the idea gains the upper hand over perception and excludes expression or narration from art.

In some works that are more manifestly conceptual, the artist even prevents the viewer from accessing the work, showing a container instead with a label, which describes the contents of the package. We cannot verify what is really in Manzoni’s containers. We just have to believe what the writing on the label of the package tells us. The shortest lines on paper bundles have been placed in a black cardboard cylinder with an orange label. The longest line is 7,200 metres long and was made from 4:00 p.m. to 6.55 p.m. on July 4, 1960, on the Herning Avis newspaper’s offset duplicator at philanthropist Aage Damgaard’s in Herning, Denmark. It is rolled up in a closed zinc container, which is sealed with lead plates and letters that describe the technical specifics of the content. The most popular work by Manzoni, Artist’s Shit (La merda d’artista, made in 90 copies and recently auctioned at Sotheby’s for EUR 125,000), also hides its contents, so that there’s constant speculation about what is really in those food cans. The secret has still not been solved, because any attempt to break open the boxes would inevitably destroy the work of art and it’s value.

The carefully prepared retrospective, with which the City of Milan honours its famous citizen, highlights the capital of Lombardy’s significance in the formation of the young artist and commemorates the 51st anniversary of his death and his 80th birthday. The show, curated by Flaminio Gualdoni and Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo, held at Palazzo Reale in Milan, follows the history of this exceptional conceptual oeuvre from the beginnings with painting, passing by the analytical experiments, right up to his last works, in which the role of the art and the artist is most accurately reflected.

In the interview with me, Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo, the niece of the artist and curator of the Manzoni Foundation as well as of the show, emphasises that her “collaboration with Flaminio Gualdoni went along very well. Flaminio is an art historian and art critic who knows the historical and theoretical context superbly, whereas I am very familiar with the collection and the works that have certain physicality. It was interesting to confront each other and to collaborate with our different competences.”

How did you distribute the roles concretely? Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo: “I was more involved with the coordination and practical work together with Christina Schenk from the Milan Municipality. We selected the works together, Flaminio just made a first consideration, on which we made some variation. The nicest aspect of this collaboration was the fact that it has been based on a continuing dialogue, and we created the sketches together with the architect Valter Palmieri during the setting up of the exposition and in the preparation phase. There really wasn’t any sort of division of labour, but a lot was achieved as a team.”

The result of this collaboration between historical, theoretical research and practical knowledge is a chronological line that helps us to understand an intense artistic evolution, which has been vanished in a very short period. At the beginning of the exposition spectators enter in contact with Manzoni’s early works, which he created immediately after interrupting his university studies to become an artist (1956–1957). This series contains abstractionist works in oils, mainly in dark tones, made partly in the dripping (drip) technique, by squashing items into the paint or now and then writing something over the top. The next series, which was created in 1957, shows a clear “Pittura Nucleare” (2) influence – the works are created from tar, oil, stones or nails with a variety of supporting materials: on paper, canvas or masonite (veneer). In these creations, which remind us vaguely of lyrical abstractionist trends – the gesture prevails over the represented content. Manzoni himself comments on this: “When the gesture has passed by, the resulting art-piece documents that an artistic fact has happened.”(3) Memories about abstract expressionist painting method and Jackson Pollock’s Action Painting vanish soon in favour of the next step, which places the concept and event at the forefront of Manzoni’s concerns. This is revealed by Gualdoni’s text in the Piero Manzoni: Life and Works exhibition catalogue: “Never again in my life I will produce paintings, I will only make events.” (4)

Manzoni transferred his searches for the identity of the artwork from the surface to the object of the painting itself, in his expanded and articulated Achromes series, consisting of white paintings on which he worked from 1957 to 1962. Evidence of this is provided in the fact that all of the colours are reduced to just one – white – which accentuates the distancing of colour and its disappearance as an element of the painting’s identity. The artist diverts our attention from colour as the carrier of meaning and as an artistic substance laid out on the surface and transfers it to the “painting” as an object and, consequently, to the theme of the identity of the art work. In a similar way to the research on Action Painting and Colour Field Painting, which was taking place in the USA at the same time, Manzoni provided allusions to ideally boundless space with the white monochrome and the structure of the material that was repeated regularly. Even though Manzoni’s white paintings have borders, their size is completely haphazard, as the achromatic (colourless) subject is really intended as an eternal repetition, ergo as a total space. Considering a picture as a boundless space, Manzoni clearly sided with Lucio Fontana’s problem of spatialism, the great patron of young Milanese artists at that time. If Fontana cuts up a monochromatic canvas to make it perceive in its spaciality, Manzoni alludes to the space’s endlessness: “Why not free this surface then? Why not try to reveal the unbounded significance of a total space of a pure and absolute light?” (5)

A number of conceptual aspects appear in the catalogue, for example, there are powerful references to ancient and modern philosophy in Manzoni’s oeuvre, which emphasise his classical education, and this is possibly a little known fact, even if there are implicite philosophical references in his works. In his essay “Achromes – Linguistic-Philosophical hypothesis”, the young art historian Gaspare Luigi Marcone points out Manzoni’s classical studies and philosophical orientation – he had read Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Sartre and had enrolled in an ancient and theoretical philosophy course at the University of Rome, which he later abandoned so that he could devote himself fully to art.

In the white paintings, the Achromes, which were initially created with chalk and later simply with clay on simple or heated canvas, everyday materials are finally incorporated, and, as Marcone underlines in the exhibition catalogue, they “embrace all of ‘reality’, which becomes a ‘different reality’, which has significance in itself, no matter whether it is natural or artificial, with synthetic fibres, rabbit fur, water-absorbent cotton, velvet, straw, polystyrene, buns and stones.” (6) Linguistically analysing the novelty of the titles of Manzoni’s works, the young researcher emphasises their connection with the Greek language, as they contain the Greek alpha privativum; therefore, the term created by Manzoni means “colourless”, as alpha annuls the word chrōma, namely, “colour” (…), therefore “colourless”, that is, “without colour”. (7) The reference to the Greek language in Marcone’s point of view provides evidence about a reference to the pre-Socratics and their searches for the original principle (Gr. archē) and indicates Piero Manzoni’s search of the original pictures.

When I asked Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo whether this new research allows one to read Manzoni’s works in a different way, to find different accents in them, she answers: “Of course, there are differing ideas, but Flaminio’s essay also offers us a reading that differs from the main one proposed in exhibitions that have taken place up till now. The connection with Classical studies was updated in particular after the publication and study of the artist’s previously unpublished 1954–1955 diary. (8) Consequently, a more philosophical link has been revealed from the young Manzoni right up until his later works, and a more accurate thread is drawn, which marks the initial concepts, active in the underground. This connection has appeared in recent years, due to the fact that new research has been undertaken.”

If the Achromes, study the artwork’s identity in a minimal key, the lines rolled up and hidden in cardboard cylinders materialise space and time as a gigantic timeline. With this stroke, Manzoni exits the space of the painting, arriving at three-dimensionality and integrating the notion of time into art. The aim – which remained unrealised – was to collect all of these lines and to bury them in various cities, thereby gain the circumference of the earth.

The latest works emphasise the artist’s participation and myth, often enough in a self-ironic manner. The identity of the artist and the art work merge, and the artwork presents an organic component of the artist’s body. The buyer no longer purchases “Manzoni’s work”, but rather “Manzoni” himself, as is emphasised by Gualdoni in the exhibition catalogue. (9)

The Artist’s Breath (Fiato d’artista), which once contained the artist’s breath, is already a deflated balloon attached to a wooden base. Egg Sculpture (Uovo scultura) is an egg with the artist’s fingerprints on it kept in a little wooden box. In the last exhibition of the Azimuth Gallery in Milan 1960, Manzoni invites visitors to “eat art”, offering boiled eggs with his fingerprint on them to be consumed. So, the Artist’s Shit mentioned previously, which is his best known work among the wider public, is therefore just a logical continuation, the natural flow of things. Waste from the artist’s organism – it’s hard to find something of less value – is preserved in a vacuum in a food can, and its price can be compared to that of gold, which is the benchmark of what is valuable (700 lire per gram).

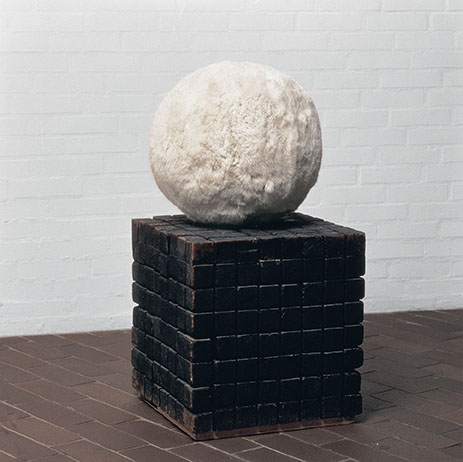

In Magic Base (Base magica) and Le socle du monde, in a Duchamp-style gesture, it is the artist who decides what to place on the art pedestal: people or even the whole planet. (10) Anybody who stands on the wooden pedestal, by definition, becomes a work of art. In 1961, Manzoni begins to sign directly some woman as living sculptures. He hands out written confirmations on previously printed forms to those who climb onto the magic base, in this way declaring them to be living sculptures.

Manzoni left behind countless unrealised ideas before leaving us so unexpectedly at twenty-nine years of age in 1963. Many years before the arrival of installations on the art scene, the Cremona-born artist imagines to extend the principal of the Achromes, all over in an entire space, filling it with white or fluorescent-coloured canvas. In Immediate Projects (Progetti immediati), which was published in Zero magazine in Düsseldorf (1961, issue no. 3), he plans to construct a “pneumatic pulsating wall and ceiling” as well as set up in a park a “little forest of pneumatic cylinders, which would extend themselves like columns”. He also wanted to exhibit “corpses of dead persons” that would be preserved in “transparent plastic blocks” as well as create a “phiale of artist’s blood”. (11)

In the last years, the frequent trips gain more and more importance in Piero Manzoni’s life, who, restless soul, builds up a network of exchange and dialogue with artists all over Europe. Marineo states: “From his diaries we found out that Manzoni hitchhiked across Northern Europe at a very young age with the desire to study everything. That wasn’t a very usual thing at the time, to just get up and travel. And indeed, afterwards, in Manzoni the artist we find the desire to get to know and tell about what is on the outside. He perceived Milan as too straight and needed just to leave all the time. It’s true, Manzoni was a very good manager and was very capable in maintaining his contacts and also in the manner in which he handled relationships. Although he was conscious, that his research was solitary, he knew, that a network of ideas was very useful. Here, something important should be mentioned as well: in reality Manzoni was always supported by his family. Obviously, he wasn’t rolling in money, but he could afford to travel while others at that time had to work and earn their livings.”

Speaking about the role of relationships in Manzoni’s life, in the exhibition catalogue Francesca Pola emphasises that despite his solitary modus operandi, he worked on projects that he managed himself with other artists, in addition to his many travels. In 1959, Manzoni founded a gallery and magazine, Azimuth, together with Enrico Castellani in which an exchange of ideas and discussions about concepts and the works of artists from throughout Europe took place. Pola describes it in these words: “Sharing and communication, idea and action, the fleetingness of relationships: Manzoni physically and metaphorically moved around this grid, from one end of Europe to the other (..). Therefore, the physical or ideal “geography”, to define the possible cartography of European art, was very important to Manzoni: this is an unusually active period of creative work (..).” (12)

In the words of Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo, his attempt to create a network with other exponents of his trade was only natural: “Maybe he went off to find places where his work would be valued and understood. We should remember that in those times a clear institutional art-system did not yet exist, therefore it couldn’t be said that his art was a real ‘attack’ on it. But he certainly was looking for his space. If existing gallery owners don’t accept us, then we try to open our own gallery.”

So many young artists after Manzoni have intuitively followed his path, namely, taken fate into their own hands and created structures that they control on their own. The Cremona artist, who grew up as an artist in Milan in the 1950s and early 1960s, paved the way for the next generation of artists. Contemporary art stands on Manzoni’s pedestal – his prophetic work merits undoubtedly wider attention and more serious research.

Barbara Fässler

Piero Manzoni 1933–1963, from March 26 to June 2, 2014, at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, Italy

(1) Piero Manzoni 1933–1963: Catalogo della mostra a Palazzo Reale. 2014. Milano: Skira, p.100. Here and furthermore – the author’s notes, unless otherwise specified.

(2) In Italian, “Nuclear Painting” – the name of an exhibition in Milan in 1950 that was organised by Enrico Baj and Sergio Dangelo, participants in the Arte Nucleare (“Nuclear Art”)

movement. In its manifesto, this movement rejected “isms”, stood against the academifying of art, and declared the breaking down of form and the finding of truth in the nucleus: “The truth doesn’t belong to you, it is found in the atom. ‘Nuclear Painting’ documents this search for truth.” From: Manifesto della Pittura Nucleare. (Translator’s note)

(3) Piero Manzoni 1933–1963, p. 67.

(4) Ibid. p. 15. He is referred to by Gastone Novelli in the work Frammento as well as in Gli scritti (Grammatica, No. 5, Maggio, 1976).

(5) Ibid. p. 71.

(6) Ibid. p. 32.

(7) Ibid. p. 32.

(8) Diario. Ed. G. L. Marcone. Milano: Electa, 2013.

(9) Piero Manzoni 1933–1963, p. 22.

(10) In French, “foundation of the world”, “pedestal of the world”. (Translator’s note)

(11) Piero Manzoni 1933–1963, p. 164.

(12) Ibid. pp. 46–47.