Tamed Chance Events

Does absolute chance (caso (1)) exist at all? Is contingency always entirely accidental or is it possible to harness it somehow? Are our decisions fully determined by our will? Do an author’s intentions fully control the development of an artwork? What is the interplay between the planned or the projected and unforeseen interference, a sudden occurrence?

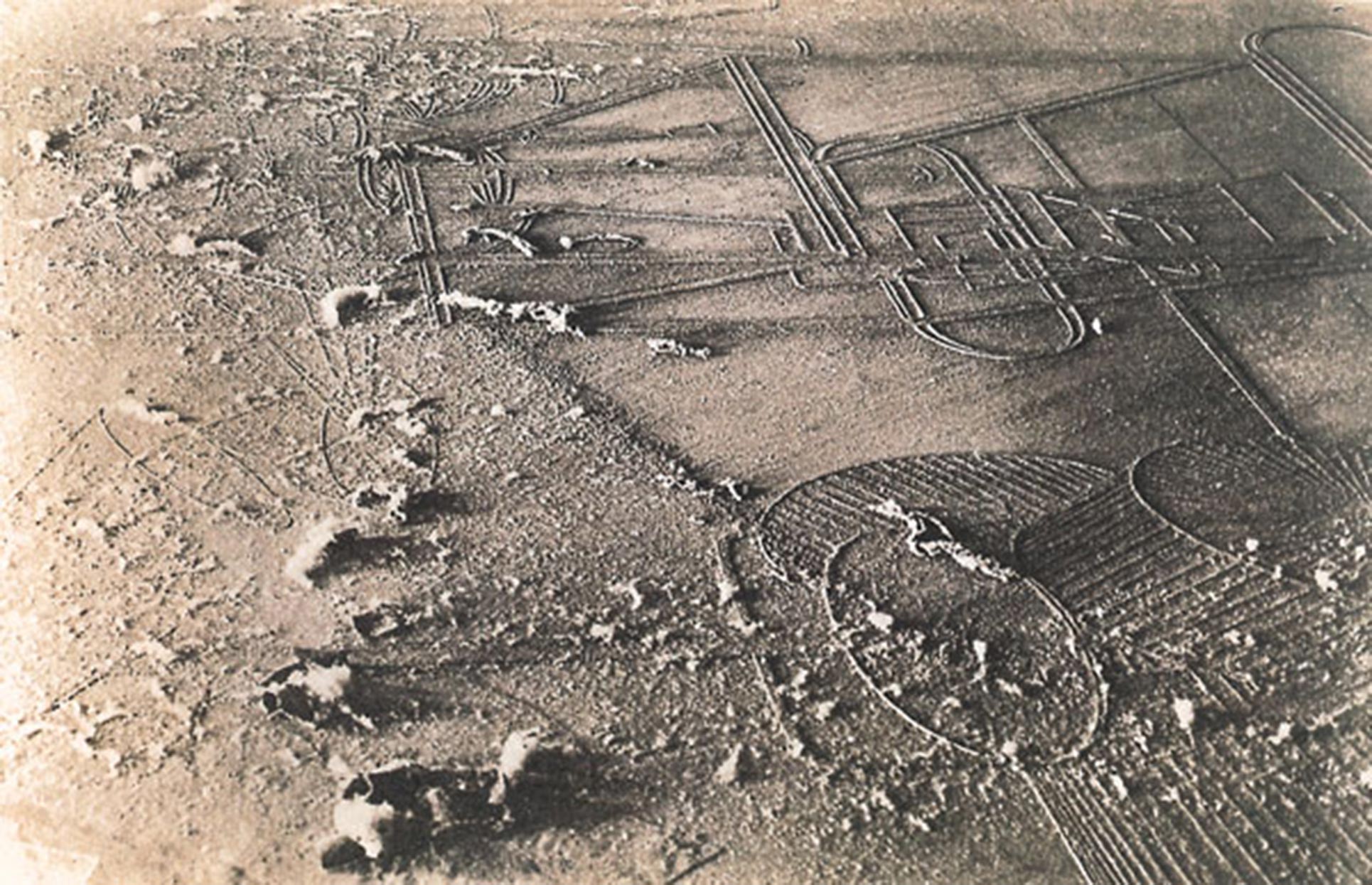

Even though in the art world the notion of caso, chance or coincidence, had been discovered and deliberately employed concurrently with other historically significant phenomena of the avant-garde in the early 20th century, the theme of the uncontrollable and related topics continue to engage the minds not only in scientific circles - let’s call to mind Einstein’s famous saying “God doesn’t play dice with the world” in relation to his quantum theory, hotly contested after the scientist’s death – but equally in the world of contemporary art, testimony to which are Man Ray’s Dust Breeding (Élevage de poussière), Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, Max Ernst’s frottages (rubbings) and John Cage’s sound experiments. In recent years, exhibitions on the subject of chance have been held all over Europe, and one hundred years after the experiments of Mallarmé and Duchamp, reflection on the mechanisms of chance is still a part of contemporary art with full rights, and continues to be extremely topical.

In some respects randomness has acquired citizenship in the cultural word, and has even become an ingredient of contemporary art. One of the reasons could be a growing comprehension of how important uncontrollable events are in the course of our life, events that often enough can derail us or make us change our course. On the other hand, we have discovered how to integrate chance elements into our plans, namely, to take the unpredictable into account, to give it space while at the same time determining its limits. Another vital aspect, as regards the role of unforeseeable events, is the way we perceive them. For a random element to find its place and acquire significance, it must be “cultivated”, the subject must notice it and recognize it. The accidental factor then functions as an aperture which makes us open our eyes and look to the external, concentrate our thoughts and absorb a part of the stimuli that reach us. Without the element of contingency in our everyday lives it would be difficult to learn something new, as our experience would be predetermined and thus also predictable. It is precisely the unexpected events that disrupt the routine, shake us up and lead to further reflection. The role of experience was regarded by the English empiricists as fundamental to their theories of cognition, as also did the 20th century phenomenologists, and I dare say that experience without at least something unexpected is inconceivable, otherwise can we continue to speak about experience at all? The subject acquiring experience would lack curiosity, would not be open to the opportunity of discovering the newness or originality of the phenomenon perceived.

Exhibitions exploring the relations of contemporary art with the element of the aleatory are found at all levels. For instance, in 2013, the Sprengel Museum of Hannover held an exhibition entitled Pure Chance: The Unforeseeable from Marcel Duchamp to Gerhard Richter (Purer Zufall, Unvorhersehbares von Marcel Duchamp bis Gerhard Richter). It began with Marcel Duchamp’s work, 3 Standard Stoppages (3 stoppages etalon), in which three pieces of thread, each one metre long, had been dropped on the floor, and the curve thus obtained was traced onto wooden templates, and ended with works by Gerhard Richter, who uses a random selection technique or coincidental numbers to determine the mix of colours. Other historic art personalities featuring in the exhibition were Kurt Schwitters with his collages and Merzbilder(2), and Dieter Roth and Daniel Spoerri with the Fallenbilder(3), in which the remains of a dinner were fixed onto a wooden table, and this snare picture was hung on the wall.

Again in Germany (only earlier – in 2010), a young artist Romeo Grünefelder organised a solo exhibition entitled Random Principle (Prinzip Zufall) in the Kunstagenten / Feldbuschwiesner gallery. On display were fundamental research experiments on the topic of chance. In the artist’s opinion, chance cannot be construed – it occurs as a disturbance or interference, and breaks with the idea of determinism according to which only something that submits to rules (that is, it can be manipulated), is to be taken into account. It also rejects the presumption that a scientific experiment is only an experiment which can be repeated, as this by definition excludes unpredictable phenomena.

In 2012, the exhibition Towards a Grammar of the Accidental (Pour une grammaire du hazard) was held at the Fri-Art exhibition space in Freiburg, Switzerland. In the white expanses of the white cube of the Kunsthalle there were on show videos and paintings created by random processes, for instance, cement thrown onto canvas (Analia Saban) or, conversely, boards removed from workplace floors, cut into equal-size quadrangles and hung up on the wall as a series of ready-mades (Erik Lindman).

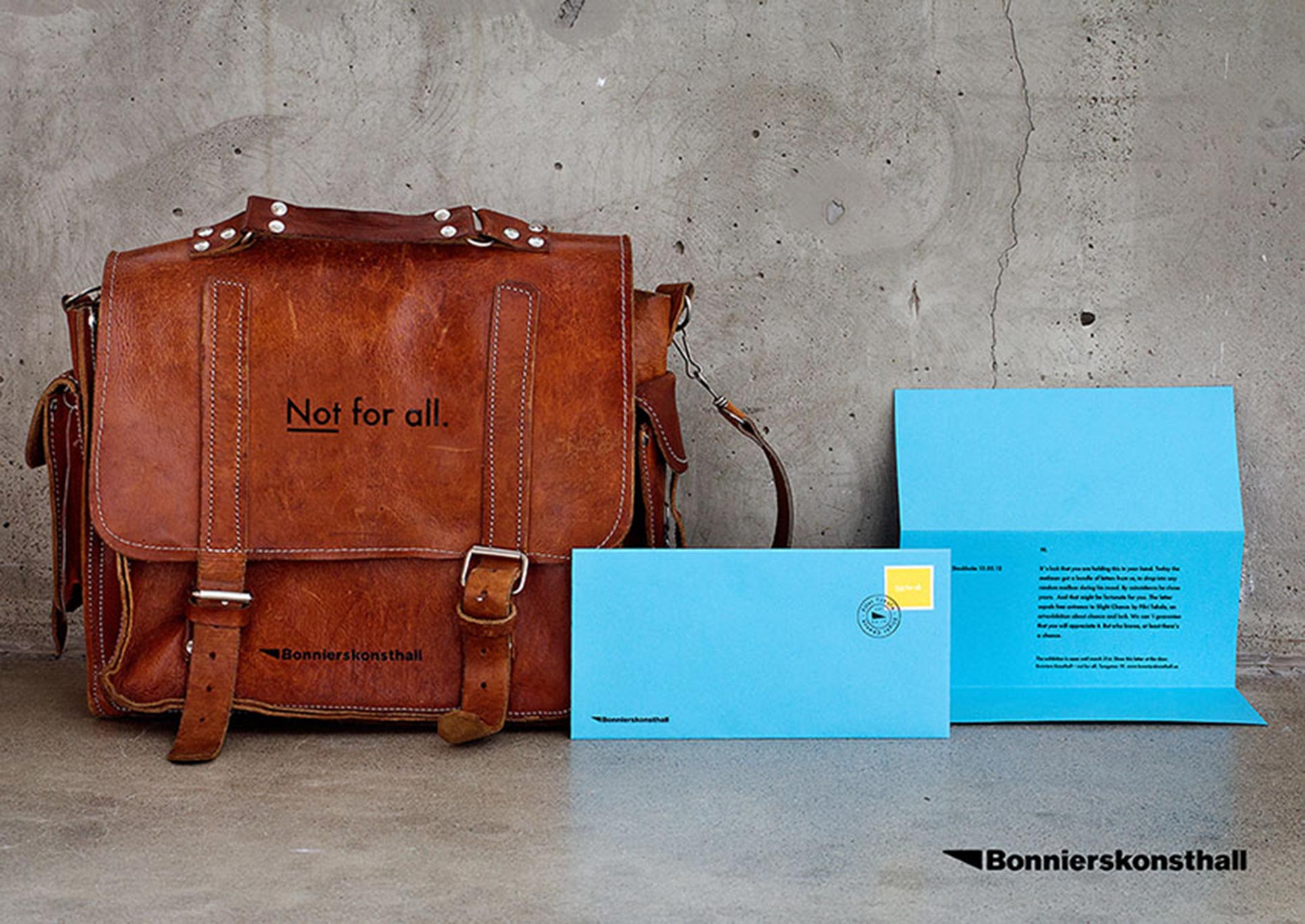

Another rather amusing example could be found in Bonniers Konsthall in Stockholm, which in 2013 used unusual methods to advertise Slight Chance, an exhibition by artist Pilvi Takala. At the marketing event titled ‘Art by Chance’, postmen distributed envelopes without names and addresses to random visitors, and e-mails were sent to addresses selected at random by a special programme.

At the Galleria Milano, on the other hand, like a bridge straddling the years 2013 and 2014 there was the exhibition Who is still afraid of chance? (Chi ha ancora paura del caso).(4) The starting point taken for the exhibition was born out of Carla Pellegrini’s idea of using the gallery collection. Curator Elio Grazioli chose the exhibits from among the works already available and added to them other pieces, classical and modern, for instance Man Ray’s Élevage de poussière, that is, a photograph of dust settled on Marcel Duchamp’s work and also Le grand verre, and an ink drawing executed by Henri Michaux while under the influence of mescaline.

On deeper scrutiny of the works on display, one notes some kind of leitmotif, like a red thread running through the various exhibits: an artist first of all devises a methodology or a rule or builds equipment as if it was a scientific experiment, and then the element of chance plays its role in this construction, in this premediated configuration which cannot be avoided. The mechanism and its limits are always clearly defined.

For Duchamp it was obvious that chance can serve as a stimulus, but on no occasion did he leave the execution of his works to chance – as if to say, whatever will be will be. As regards 3 Standard Stoppages he admitted in 1913: “It was a great experience. It was important that I could welcome a random inspiration – many of my most carefully organised works have been inspired by chance meetings.”

The exhibition “Chi ha ancora paura del caso” contained various examples of situations in which chance’s “range of action” is limited. For instance, the sheets of Amedeo Martegani’s work remain pasted to the bottoms of tea cups, while Japanese painter Kazuo Shiraga paints with his body, applying it as a brush – he has suspended himself from a rope which precisely fixes the perimeter of his action. The splashes of photographic acid by the famous Vincenzo Agnetti have left ornamentation on the surface of photosensitive paper of exact dimensions that the artist had chosen and prepared. In fact, there is much greater unanimity about the rules of the game than one might think. As regards the creative work of Marina Ballo-Charmet also, I would also say that her steps are intentional, she knows where her path is leading. She bustles to and fro around her flat, doing her usual household chores, although she justly asserts that we have no control over all our daily comings and goings. One could say that her movements match the intentions for the work to be done; her conscious actions are in keeping with the chores she has to do. A video camera affixed to her belt traces the trajectory as defined and considered by the artist. The “margins of the game” of chance have been drawn, namely, chance is enclosed within time and space, it has been shown its place in the system that the artist has devised. As though tamed.

Korean artist Jae-Eun Choi buries paper squares in various locations across the world, lets them rest in peace for four years and then goes to find them and digs them out. The result is astonishing, because the soil colours the paper in various shades and hues. The artist’s intentional systematic action has yielded a completely random outcome.

Guy Debord’s work in turn is a “psycho-geographical drifting” in city streets – the individual allows himself to be led onward by everything encountered by chance. Debord believes that to exit from yourself, it is enough to raise your eyes just slightly upwards and yield to the lure of detail. Oscar Dominguez, however, creates his monotype by crumpling together two pieces of paper. Artist Tano Festa drops confetti onto piece of fabric of certain dimensions, and David Mosconi does something similar using gemstone dust. Two artists – Nicola Pellegrini and Gil Joseph Wolman – use sticky tape. Nicola “fences in” the surrounding space, while Gil pastes together newspaper letters. Luca Vitone creates a portrait of Rome by keeping a white canvas on his balcony for months. The dust and other substances in the air gradually create a design – the lines of the tiles underneath press into the canvas like in a surreal frottage.

One can put forward a hypothesis that it is not so much a matter of an uncontrolled chance event, but rather of a kind of scaffolding, an experimental construction in which chance will play its role and decide the final outcome. An artist’s intention therefore determines space, time and the method of random action. It is a matter of tamed chance which is controlled within limits, or perhaps to put it better, one creates the opportunity for a meeting, interaction with the external world, a staged coincidence.

interaction with the external world, a staged coincidence.

When asked about the idea behind the exhibition, curator Grazioli expresses himself as follows: “My departure point is the idea of chance as a meeting. Duchamp called it a “rendezvous”, while for Breton it was “objective chance” which is an oxymoron in the sense that you come across something seemingly accidental, but then it remains in the focus of your attention, and you realise that what you encountered was not accidental, or else you realize the significance of the meeting in retrospect. Chance has come forward to meet you. It’s not just you projecting thoughts towards the events that happen. I would define chance just like that – as a meeting between intention and conincidence, something that occurs.” To the question of whether he thinks that absolute chance exists, and if yes, then how he would define it, the curator replies: “That’s a philosophical question indeed. First you need to try to define chance in order to answer. In my opinion, chance exists, however, in the sense as has been illustrated by contemporary culture – from psychoanalysis to science. It is an active chance, it is not senseless, not absurd, not the opposite of necessity or an antithesis. It is the kind of chance that seeks its own ways which we interpret later as something meaningful. We always weave with the elements of thread and yarn, clues, associations, contrasts, and thus we extract meaning from all that, one might say, even find destiny in it. Chance fascinates me by its openness, the fact that is has some other logic, different from deductive, linear logic. Also in relation to language. We are unable to use language at random. There is always a subject, a predicate, objects, adjectives that agree with nouns, you cannot throw them about in a text any old how. But in the visual realm you can. Let’s say, chance interests me from this aspect.”

We also encounter the same dichotomy between intention and chance, that is, between the planned and the unpredictable elements, in curators’ daily tasks, when they have to select works. Hence we could say that a curator’s work is anything but random. In this regard, Grazioli affirms: “The most important part of a curator’s work and which, by the way, more often seems to remain in the shadow, is to render visible the idea and theme of an exhibition through the arrangement of the display. The curator carries some of the duties of a scenic designer, is responsible for the visual. It is not so much about a quest for ideas, an examination of the most topical ideas or writing a text, but rather about setting up an exhibition that comprises visual elements. This seems to me the most neglected aspect in group exhibitions which I see around various locations.”

Even though the layout of the exhibition could seem totally random – indeed, the works dance on the wall as if in an exhibition of Constructivist artists – nevertheless, as Grazioli explains, the placement of the works has been pedantically thought out, down to the minutest detail. “In fact, the set-up was inspired by a Mallarmé text which is the origin of the contemporaneity of the theme. “A throw of the dice will never abolish chance” (Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard) is the first ever visual poem with a very particular visual solution(5). Thereby the gallery walls function as the pages of Mallarmé’s poem. The poem in fact contains many lines with omissions and gaps. This creates cross-references leading to a new story, new opportunities. This is what I wish to put on show and discuss in greater detail. Not to tell a linear story, but to offer something like a map that shows a more comprehensible, open, associative scene. With all its contrasts.”

While chance unexpectedly interrupts and interferes with our daily routine, artists and curators know how to take advantage of these by building a sports hall where a ball can hit against walls and fly in any direction. The “appointment” with chance is not an oxymoron: the accidental exists only wherever we are able to appreciate it as an essential element of our experience, and consequently also where we know how to wait patiently. Like a cat in front of a mousehole.

Barbara Fässler

Translator into English: Sarmīte Lietuviete

(1) Here and henceforth – translator’s note. A word with multiple meanings, also meaning ‘occurrence/instance’, ‘case’, ‘grammatical case’, ‘fate/destiny/fortune’. It is the same word with which Wittgenstein opens his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: Die Welt ist alles, was der Fall ist. Both in German and Italian the word is etymologically related to falling (Fall<fallen, caso<cadere) and hence is also translated as ‘coincidence’.

(2) Collages with elements of cubism and expressionism, “dadaism in art”. Schwitters’ first Merzbild was done in 1919.

(3) Fr. tableau-piège, Eng. snare-pictures – assemblages or accumulations, “a frozen moment of reality”, featuring household items, fragments of dishes, food leftovers etc. glued onto a hard surface and lacquered. First appeared around 1960.

(4) It seems like a pun on the title of Edward Albee’s play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962).

(5) This is the first so-called graphic or visual poem in French literature, first published in Cosmopolis magazine in 1897. The Latvian reader will be familiar with Guillaume Apollinaire’s calligrams, see the poetry collection Gājiens (Rīga: Liesma, 1985), translated by Klāvs Elsbergs.