The Dramaturgy of the Moment

“It has always seemed to me that really artistic, truthful ambiguity – if we can use such a paradoxical phrase – is the most perfect form of expression. (…) So, I think that, conversely, the literal, plain, clear statement is, in its own way, a false statement and never has the power that a perfect ambiguity might.”

An interwiev with Stanley Kubrick in 1960, first published in The Guardian, 16 July, 1999

This ambiguity, at the same time critical and unstable, pursues us everywhere in the unlimited photographic work of Stanley Kubrick and makes it difficult to maintain our position without calling into question our convictions. The Library of Congress in Washington and the Museum of the City of New York hold no fewer than 20,000 negatives of shots taken by Kubrick between the ages of 17 and 22 years for the American magazine ‘Look’.

The exhibition at the Palazzo della Ragione in Milan, curated by Rainer Crone, reveals a world orchestrated by the acute viewpoint of the film director, until now completely unknown to the public: the 180 photographs – silverprints in black and white – have never been printed before, nor have they ever been exhibited anywhere.

The ambiguity of which Kubrick speaks plays subtly on a number of levels: on the subjects as well as on the formal rendering of the photos, which are for the main part square shaped (from negatives 6 x 6).

We are in the immediate postwar years, re-awakening from some of the most traumatic experiences in the history of humankind, such as the Second World War, the Holocaust and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the future cinematographer never gets tired of reminding us painfully of the fragility of our existence. He confronts us with a world which had just realised its own extreme precariousness, a world which only a short time before had emerged from catastrophe.

There are many situations that are able to express this powerful sensation of danger, not only concretely, but also as metaphors. The exhibition opens with a close-up of an arm which is pointing a pistol in the direction of a ‘paddy-wagon’ carrying away people under arrest, but of this we only see a faint triangle which cuts the square along the diagonal. The series of snapshots from the circus leave us suspended in a situation of heightened tension as well.

For example, there is the image of the tightrope walker who is balancing on a bicycle with two trapeze artists hanging from it. The circus director, who seems to be glued to the right hand edge in the very foreground is shouting in the direction of the artists, and pushes to the extreme the sense of danger inherent in the scene. In another masterpiece, on the contrary, we may observe a little blonde girl with a tiny newly-born leopard in her arms: ingenuous innocence prey to programmed high risk.

Remaining in the world of childhood, we witness an absurd scene of two little boys who, bursting with laughter, are playing tightrope walkers on the railtracks where the train has just passed by. There are also acrobats, caught in midflight leaping in the air, or teetering in situations of instability, there are elephants or enraged tigers. This representation relying on the precariousness of the subjects is not surprising in the world of the circus, but when it extends into the fashion milieu and university environment, however, it becomes something more unusual.

This occurs, for example, in the shots where Betsy von Fürstenberg has fallen off a bicycle, is climbing a tree or dancing on a low wall at the edge of an abyss. In another instant, this time at Columbia University, we witness a chemical experiment which threatens to blow up the entire building sky high. Also tending in a similar direction is the photograph of a woman, still at Columbia, who is descending down the stairs, carrying a dangerously high pile of books, so high that it is preventing her from seeing where to put her feet. This image could vaguely hint at the dramatic scene in ‘Battleship Potemkin’ of Eisenstein, where the pram flies down a stairway at high speed, or, at a formal level, the photographs of stairs by Rodchenko which, because of the unusual angle, become abstract pictures.

The parallels with the Russian Constructivists become even more powerful from the purely formal point of view, if we examine the construction behind the images. Certainly, Kubrick depicted situations that he met by chance, but all the same, it’s impossible not to suspect – given the extreme precision of the shots – that these found objects may have been consciously manipulated and staged by the author. The images are often constructed following rigorous geometric forms: thus the square could be cut through the centre either horizontally or vertically, at other times, however, in three slices, or otherwise very often cut along the diagonals.

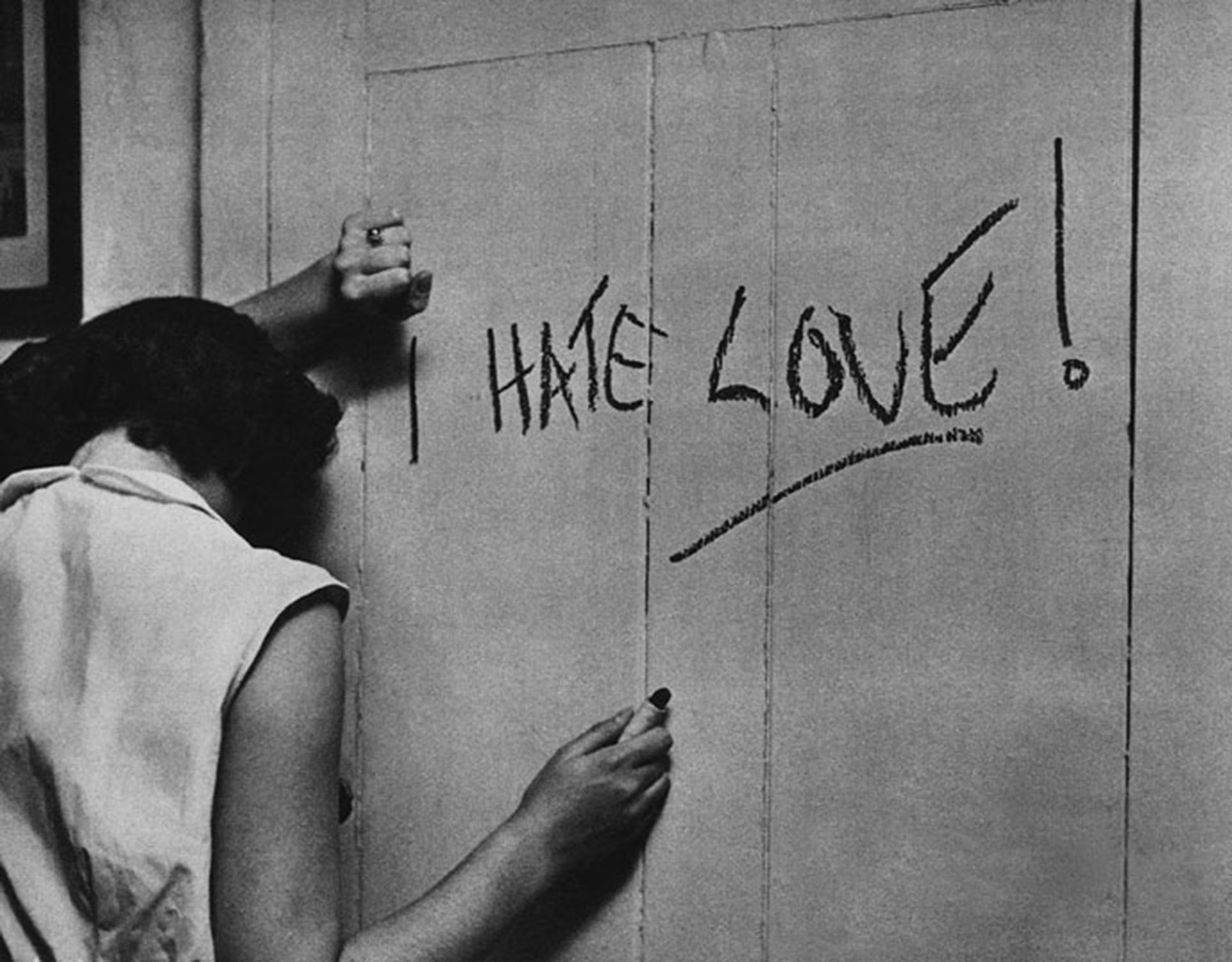

The fact that the architecture of the representative plane has been meticulously projected is an important indicator sustaining the thesis that photography cannot claim to produce clones of a presumedobjective reality, or of whichever ‘truth’. Reality in itself doesn’t exist, but we are continually constructing our world ourselves, through our gaze, our thoughts and ultimately our shots. An unambiguous world, like any literal affirmation – we have seen it – is, according to our author, a false statement. The truth, if it were to exist, should therefore be sought in a multiplicity of meanings, in ambiguous situations, or in apparent contradictions. Stanley Kubrick demonstrates this well in the image which perhaps encapsulates, best of all, the profundity of his thought. We see a girl from behind, lowering her arms after having written on the wall in lipstick: “I hate love”.

Already Hegel had taught us that contradictions make the world go round. It’s not incidental, therefore, if after 5 years of intense activity as a photo journalist, static images for Kubrick were no longer enough for expressing thoughts of such complexity. Thus he turned – as we know – to the cinema, which allowed him to perfect the language of drama, to elucidate the very deepest existential mechanisms through his stories.

Examined from up close, moreover, one discovers that the ‘cinema’ is already present in these photo shots from the second half of the 40s: there is, for example, the one where Mickey, the shoeshine boy, is admiring the poster for ‘The Jungle Book’ at the entrance to the cinema. Often the subjects are represented by Kubrick as if they were divas of the big screen. This holds not only for the shoeshine boy, but also for the various shots which portray a travelling couple, for example, in their hotel room.

But not only. Kubrick the filmmaker is revealed above all in his wish to tell stories through the serial structure of his photo-shots, which allow us to catch a faint glimpse of an embryonic time line. This method of proceeding is born of an explicit request of the magazine ‘Look’, which published the works of Kubrick: all its photographers were encouraged to follow their subjects, in this way creating a kind of photo-story, a primitive form of pictures in movement.

Closely linked to the problems of representation (if not their foundation) is perception: the everpresent principle in Kubrick’s search, which accompanies him from the phase of photographer to the one of the film-maker. There are almost no shots in which the principle of vision has not been thematized, and where the views do not pass, designing lines across the space, which often even aim outside the frame to enlarge, by doing so, the representative space.

The creations of Stanley Kubrick tell the story, therefore, of our way of perceiving and working out surrounding reality, of the visible and invisible, of the manifested and the hidden, and ‘last but not least’, our eternal desire to grasp and get to know our world and its inverse.

Barbara Fässler